One of the real difficulties in nature conservation is the basic fact that humans have short lives and shorter memories.

We instinctively assume that the way the countryside “should” look is … how it looked when we were young. Obviously, it had been that way since time immemorial, at least since the year 1 B.M. (where B.M. means “Before Me”). In Feral, George Monbiot calls this “Shifting Baseline Syndrome” – each new generation sets the baseline to the time of its own youth: we imagine our childhood landscape to have been just right, good, and natural.

Only it wasn’t. Our limited time horizon obscures the fact that the countryside has been changing continuously since Roman times, indeed since the Stone Age. Forests have been felled, making way for fields, towns, and roads. Already by 1000 AD, most of Britain’s forests had disappeared, and our larger forest animals like bear, wolf, lynx and wolverine were disappearing with them.

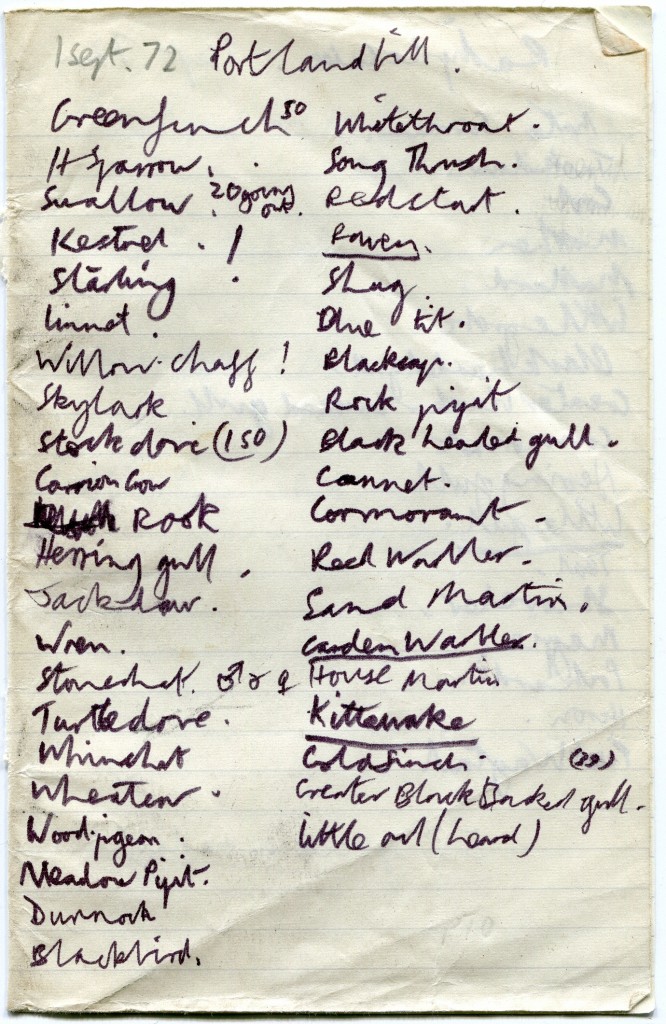

But even in a single lifetime, the loss of once-familiar species is shockingly evident. I had a small reminder when I found one of my birdwatching notebooks from my schooldays. We had been on a Natural History Society trip to Portland Bill, where we stayed in the old lighthouse, a bird observatory in a fine location for counting (and trapping and ringing) arriving and departing migrants. A group of us walked out in the bright sunshine on 1 September 1972, and I listed what we saw.

I was pleased to see a Raven, a Garden Warbler, and a Kittiwake, as I would be today, though all these species are doing well. I was reasonably pleased to hear a Little Owl, something that would now be rather special. I was quite unsurprised to see 20 House Sparrows, and I don’t seem to have found the Turtle Dove or the Redstart at all remarkable. Either of those would now be close to the highlight of the year: and the Song Thrush too, once a regular garden bird, has become really rather uncommon. Then there are the Skylark and Whinchat, which I gave no more notice to than the Linnet, Jackdaw and Stonechat; and the Sand Martin too is declining alarmingly. The 39 Goldfinches, on the other hand, were somewhat remarkable to me then, but I see nearly as many in flocks around the quieter streets in town. I didn’t think the presence of 5 warblers worth noting, though at least that isn’t too terribly difficult to achieve today – just a matter of going to a reasonably decent nature reserve, as there won’t be many species on farmland (you’re lucky to get Chiffchaff and Blackcap, really). The mixture of farmland species, birds of open moorland (Meadow Pipit, Wheatear), and coastal species (Shag, Kittiwake, Rock Pipit) is far more remarkable than I realised at the time, and is probably characteristic of those headlands where migrants congregate.

It would be interesting to repeat the walk early in September (or in the spring migration) and see what we’d see. I think there would be fewer species. And a lot fewer sparrows.