“We’ve had a creationist … babbling away in the comments. He’s not very bright and he’s longwinded, always a disastrous combination, and he tends to echo tedious creationist tropes that have been demolished many times before. But hey, I’m indefatigable, I can hammer at these things all day long.”

Thus speaks Pharyngula (P. Z. Myers), most indefatigable of science (or should that be, anti-nonscience) bloggers. He’s been at it since 2002, and in that time he’s written about a huge range of topics.

On the way, he’s acquired a nonscience enemy who’s closely enough stuck to him (opposites attract) to have an antiblog of the same name. It’s almost a fanpop website, complete with photo portraits, CV, and a section called ‘What the heck is a pharyngula?’ which actually answers its own question. It’s a stage in the embryonic development of vertebrates, following the more familiar blastula, gastrula and neurula stages (pay attention at the back there).

He has even, by dint of writing accurately and entertainingly, and by speaking truth to twaddle, acquired his own Wikipedia article, quite a feat since generally self-published blogs are considered inherently “non-notable” by that august establishment. My spellchecker just suggested “Windpipe” for Wikipedia, not a bad try. Anyway, Windpipe tells me he won the 2005 Koufax (who?) Award for Best Expert Blog, and he certainly deserves it.

Pharyngula delights in natural history, perhaps especially in octopuses — a search for “Friday cephalopod” is entertaining. Go on, here’s one that he liked.

Pharyngula readers are also treated to Monday Metazoans. Try it. There really are more things in heaven and earth …

But too much of Pharyngula’s time, and the world’s, is taken up with kicking “Bad science” – he also has categories for “Bad Science”, Creationism, Godlessness, Denialism, Kooks, and Weirdness, and I expect I missed a few more. It’s a lot of energy.

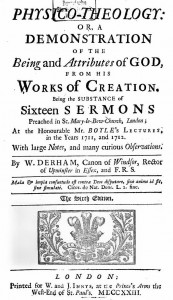

I’ll write about the history of it another time – the Argument from Design thing has been going on since at least 1713, when the Revd. William Derham published his Physico-Theology.

The curious thing about physico-theology, natural theology, intelligent design, Paleyism or what have you is that it is a circular argument. There’s assumed to be a Creator. The Creator is assumed to be good. Things in nature are seen to be well-adapted, e.g. the wings of birds are well adapted to enable them to fly. Since birds have been created, the Creator must be good, and must exist. Errm, something not quite right in this argument… it’s logically hopeless to assume what you’re trying to prove, regardless of any external facts. Assuming for sake of argument that there is a good Creator, the existence of birds with well-adapted wings says precisely nothing about that Creator. The birds might always have existed, or might have been created in a Manichean universe by an evil being, or might have evolved all by themselves, there’s no telling just from the excellence of adaptation of the wings on the bird.

Curiously, “the survival of the fittest” looks at first sight like a circular argument, and intelligent writers like John Stewart Collis have fallen into the trap of thinking that’s what it is. But it isn’t. Darwin didn’t say that the ones that survive, survive, so species evolved — the first part says nothing, and evolution doesn’t follow. Darwin did say that the ones that don’t survive, don’t have children. It’s a what-happens-in-the-next-generations argument, and that breaks the circularity. Or to look at it from the present back to the past, back all the way to the origins of life on Earth, each thing living now is descended from parents and ancestors which survived long enough to reproduce, while countless others failed to do so. Some were simply unlucky: in Darwin’s words, nature is prodigal: tremendously wasteful. Others were just slightly less well-adapted, just slightly less likely to survive long enough to reproduce, and did not so survive. The result: in each generation, the offspring carry the genes of the just slightly better adapted. Darwin was right, it is a prodigiously wasteful mechanism. A more wasteful approach could not be devised — you generate a tremendous variety, and in each generation you throw almost all of it away. Out of thousands of eggs in frogspawn, only a few will become adult frogs; out of tens of millions of eggs of the Atlantic cod, only a few will become adult fish that breed. “Only the fittest survive”: not exactly. Many perfectly fit fish are unlucky. But the fit ones are on average luckier than the rest. It’s a slippery argument, though not really complicated, and it has to be stated carefully. But it has proven to be a pons asinorum for far too many.