The artist Gail Dickerson creates her paintings through what must be a unique combination of observation of technological artefacts and the deliberate application of natural materials through the recreation of natural processes.

Thus it is no accident that her paintings have a natural, accidental, chaotic look: they are created from actual earths, muds and clays of many different colours – real earth pigments – and they are allowed to form themselves on to the canvas through processes that recreate the basic geological processes of erosion (of rocks) and deposition (of sediments). Gail crushes and grinds the earths to form usable pigments: of course she also transports them to her studio, just as glaciers transport rocks as ‘erratics’, grind and crush rocks to rock-flour as moraines and the thick, sticky boulder clay that covers the little hills of Southeast England.

Then she mixes the pigments with water and a binder to make simple paints, and pours them on to her canvases, where they flow, evaporate, diffuse, and arrange themselves into the beautiful fractal patterns of sand-dunes, beach ripples, estuary channels, or just puddles seen in her paintings.

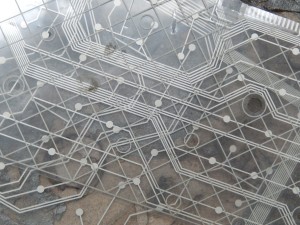

The other input to Gail’s paintings is the high-speed world of modern technology. She strips printed circuit boards from abandoned devices (which with today’s instant obsolescence often means only a couple of years after they were made) and draws their patterns on to her canvases. In an earlier phase of her work, she actually placed assorted components on the canvas and allowed them to leave their “shadows” behind as pigments flowed over and around them.

Circuit boards form patterns as their wiring is optimised to follow shortest paths for the many interconnections, as well, sometimes, as to provide sufficient spacing to reduce electromagnetic interference between the rapidly oscillating currents in the tiny wires. (Gail commented that these technical terms would make good names for artworks.) Gail had redrawn or imagined suitable wiring layouts on transparencies, and it was hard to tell her imaginings from the real thing, so convincingly did they wander in apparently optimal directions between components.

Gail then transfers the circuit layouts, suitably transformed, to her canvases, where they and the variously oozing, evaporating earths in their chaotic patterns do a dance together, neither taking over, neither too prominent.

For me, it’s a figure of the modern world, where man makes use of nature – ColTan ore turning into electronic components, sand turning into silicon chips, oil turning into the plastics and resins of insulation and circuit boards (after all, all materials are ultimately from nature), and the manmade patterns of thought, algorithmically-designed electronics, squeak and chatter at their inaudibly-high GigaHertz frequencies (as recently as 1994, we all had slow old modems that audibly squeaked when connecting to the Internet to retrieve emails and briefly browse a few small klunkily laid out early web pages, how quickly things change in that world).

For me, then, Gail’s paintings, made in nice old buildings a stone’s throw from the Shard, the river, and Shakespeare’s Globe – inevitably, just about to be turned into expensive new apartments or offices – beautifully sum up modern life. We are still rooted in Nature: our tailless ape ancestry of course, our drives for food, water, sex, power, sleep absolutely apelike; while another part of us races ahead in the bustling city, now sprawling across the river from the City of London to the Docklands and down onto the South Bank around London Bridge and the suddenly burgeoning glass towers of Southwark. Alexander Pope had it right in his Essay on Man when he describes us as

Created half to rise and half to fall,

The glory, jest, and riddle of the world.