London does look beautiful at night when seen across the river, whether you look at the classical outlines of St Paul’s Cathedral – not the one that Shakespeare knew, of course – or at the brash towers of the City, the slick take-your-money confidence of quick men who know all the patter and have the steel, glass and concrete to prove it.

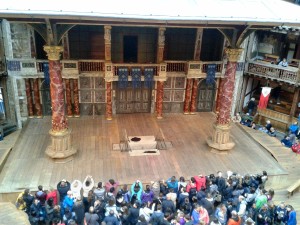

Everyone knows Shakespeare’s “All the world’s a stage” speech from As You Like It, and when that appears on stage as it did yesterday, it’s striking to see how well the strutting and fretting of the actors can work on that big wooden rectangle “in the round”, surrounded by the beautifully reconstructed circle of the Globe Theatre with the long-suffering audience standing in the pit. As you can see, we decided on the more comfortable course of seats in the upper gallery, affording a fine view of the pit audience reaction as the actors come right up to them, sit with legs dangling over the edge of the stage, walk round behind them, or actually push straight through the crowd.

But perhaps the Nature’s Book aspect of As You Like It is not so obvious:

Nature speaks to the (banished) duke in the Forest of Arden (Act II, Scene 1): the trees talk, the brooks babble as if reading, the stones deliver sermons. Here is the voice of Nature with a capital N, “the classroom, the library, and the church“, figured if not quite personified as pastoral wisdom.

In Shakespeare’s time, the Book of Nature was a “theological commonplace” (Paul J. Willis; JSTOR, library or subscription needed). The curious concept of nature more or less literally as a book

‘”originated in pulpit eloquence, was then adopted by medieval mystico-philosophical speculation, and finally passed into common usage,” where it was “frequently secularized”‘.

Nature is described as good in Genesis chapter 1, and Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Romans argues that God’s power is seen by the creation of the world and in his works. Willis observes that this is a bit difficult to reconcile with Paul’s assertion that nature is utterly fallen and sinful, but no matter. Willis concludes by noting the “often recurring comment” that As You Like It mocks the pastoral while basically enjoying the pastoral quality, and suggests that Shakespeare similarly mocks the rather lofty Book of Nature theme “without tossing it aside”. The comedy comes from realizing that the forest is an imperfect divine text, just as we are “faulty readers” of that book. “The result in this rich comedy is the book of nature as you like it, a forest that exposes both God and man.”

Having written a book on the English view of Nature, I find Willis’s analysis – and Shakespeare’s treatment – extraordinarily good.