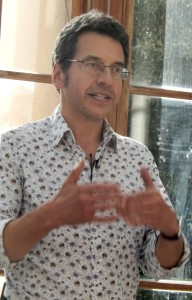

Yesterday I went along to Kew Gardens’ new book festival to hear George Monbiot, the author of Feral: Rewilding the land, sea and human life (Penguin, 2014). He was genuinely inspirational.

We sat down in neat rows on elegantly stiff, lightly-made wooden chairs in the beautiful Nash Conservatory, the sun streaming right into our eyes; Monbiot’s first words were to apologise humorously for the rather bright lighting. The two large computer screens displayed the festival’s welcome screen, and stayed that way: Monbiot spoke without slides, and without notes. He was clear, sharp, warm, and where appropriate really quite entertainingly rude about government policy.

Britain’s “trashed” uplands

He told us how his excitement at moving to the Cambrian Mountains turned to puzzlement and then despair as he realized there were no trees: no birds: no butterflies: no bees: no flowers except Tormentil, indicator of poor soil. He directly and simply told us complicated stuff, like the Structural Heterogeneity of the rainforest, a whole architecture of ecosystems with multiple niches for species of every description. He reminded us that Britain has less tree cover than almost anywhere else in Europe – 12% against an average of 37%. His mountains had been shagged to death by sheep, ruined by the white plague; other mountains (Scotland, say) had been just as well trashed by management for shooting grouse or red deer. Britain had the second biggest landholdings of any country – after Brazil. Why? Because farm subsidies reward the largest landholders, the oil sheikhs and Russian oligarchs, the world’s luckiest landlords, paid for doing nothing but keeping the land in “agricultural condition”. And that meant? Keeping it free of what the bureaucrats call “permanent ineligible features”, in other words, trees. Britain’s mountains are wet deserts, profitable only to the rich. And they are paid to keep the land species-poor.

Even the nature reserves have “key indicator species” (Monbiot was really warming to his theme now, putting the boot in) like Red Grouse, Ring Ouzel, Skylark, Meadow Pipit: the few birds that thrive in bare open moorland (and there were hardly any of them, he said). Montgomeryshire’s claimed “really wild” jewel in the crown reserve was “identical” to the rest of the cold wet desert. It, like the rest of it, was maintained by a programme of cutting, burning and grazing to prevent trees and bushes from taking over. The “undesirable species”? They were, erm, native trees like Hawthorn and Birch, the pioneering colonisers that pave the way for all the trees of the forest, all the way up to, um, the beautiful natural primary forest of the Wildwood, complete with glorious epiphytic ferns like Polypody, great trailing beards of lichen, all the mosses and liverworts and flowers and invertebrates and beasts of every size that you’d find in a rainforest. It’s a circular argument: you need grazing to maintain “favourable condition”; and that is measured by indicator species which are the ones found on bare moorland; which you’ve defined as what favourable condition is. Only, that isn’t what the Eurocrats actually asked for: they specified “favourable ecological situation”, which might mean … wildwood. Quite the opposite.

Protecting the ranchers from the rainforest

Now for the sting: if the ranchers of Brazil start a program of cutting, burning and grazing to destroy the rainforest, leaving bare meadows for their cattle, there’s an international outcry. But in Britain, it’s the required management regime for our best nature reserves! We’re protecting the ranchers from the rainforest. Why is mid-Wales bare and open? Because for 200 years it was devastated by lead mining; and after that, grazed to nothing by sheep. The white death only need to be present at one sheep per ten Hectares (hardly any, basically) to kill all the new tree seedlings: young saplings are delicious and nutritious, and sheep greedily and selectively seek them out.

Well, I’m not going to try to recap the whole talk, let alone the whole book, which I’ve already reviewed for you. Rewilding, Monbiot says with simple and direct plausibility, is informed by Remembering. And our memories are terribly short. Back in the 18th Century, Oliver Goldsmith described the massive shoals of Herring in our waters; harried by enormous numbers of Tuna, Porbeagle, Sperm Whale, Fin Whale. Yes, there was in the past few centuries, recorded by careful scholarly intellectuals, a thriving Tuna fishery at Scarborough. Not the Tonnara in Sicily, now defunct; not the Tuna fishery of Monterey Bay with its Cannery Row, now a marvellous Aquarium (I have the T-shirt to prove it); but right here. Like our coast-to-coast temperate rainforest, it’s practically all gone.

Trophic cascades

BUT… we can have it back! “Amazing things can happen”, said Monbiot. There are Trophic Cascades, life pouring down from the top in an ecosystem. How? The classic example is from America’s Yellowstone National Park. The wolves were removed in the 1920s to “improve” on nature, allowing more deer (and better hunting). Only, it didn’t work out like that. The park, deprived of the wolf, became steadily poorer in wildlife. Then in 1995, after lengthy argument (very lengthy argument, in fact), the wolf was brought back in small numbers.

The effect was dramatic. Within six years, the trees were FIVE TIMES taller. The wolves had scattered the deer from their grazing haunts down by the rivers. Saplings sprouted. Trees shot up. Beavers felled trees to make dams and lakes. Waterside plants flourished. Fish, invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles and muskrats appeared all over. The wolves killed coyotes. Small animals appeared all over. The trees stabilised the banks of the rivers. The rivers meandered less; erosion patterns altered. Bison multiplied among the larger trees. Fruiting shrubs blossomed and bore berries; bears ate quantities of them, and fish. The wolves changed the landforms, planted trees, made flowers bloom. Everyone, including professional ecologists, was astonished.

Rewilding Britain

What could we have here? Getting the moose, bison, bear and wolf back may take some time here in tightly-buttoned Britain. Elsewhere in Europe, wolverines are coming back from the far north; millions of beavers are making dams in dozens of countries; lynx are being reintroduced with minimal fuss. Everyone except us thinks it’s NORMAL. Everyone except the British governing elite (and their landowning friends and relatives) wants to see beavers and wild boar in our countryside: lynx, too.

Can we have wildlife and people? Sure.

Can we have wildlife and subsidies for grouse moors and a “stupid” Common Agricultural Policy? No. Even the supposedly “green” part of the CAP is insane – we pay 55 billion to farmers to do nothing with the land (except destroying trees), then we pay them a bit more to put a tiny bit of wildlife back on a tiny part of it: and even that part is basically worse than useless.

Conservation sites have to be resilient, argues Monbiot, self-willed, running nature’s own processes, if they are to survive the shocks that are coming. All we have to do is to let nature get on with it.

Hope

At the end we all trooped to a table where Monbiot signed our copies of Feral (here’s my book review), in my case a clean but pretty well-thumbed copy. He wrote “To Ian, with hope, George Monbiot”, and I went home in the sunshine thinking, yes, with hope: “conservation” sounds worthy and dull, like aunties with conservatories in their garden, or conservative opinions, or carefully conserving dusty artefacts against moth and museum beetle. But hope: hope that Britain will gain new and better kinds of nature reserve, full of deer, and beaver, and wild boar, and lynx, a sparkle of excitement at glimpsing what the wildwood was really like.