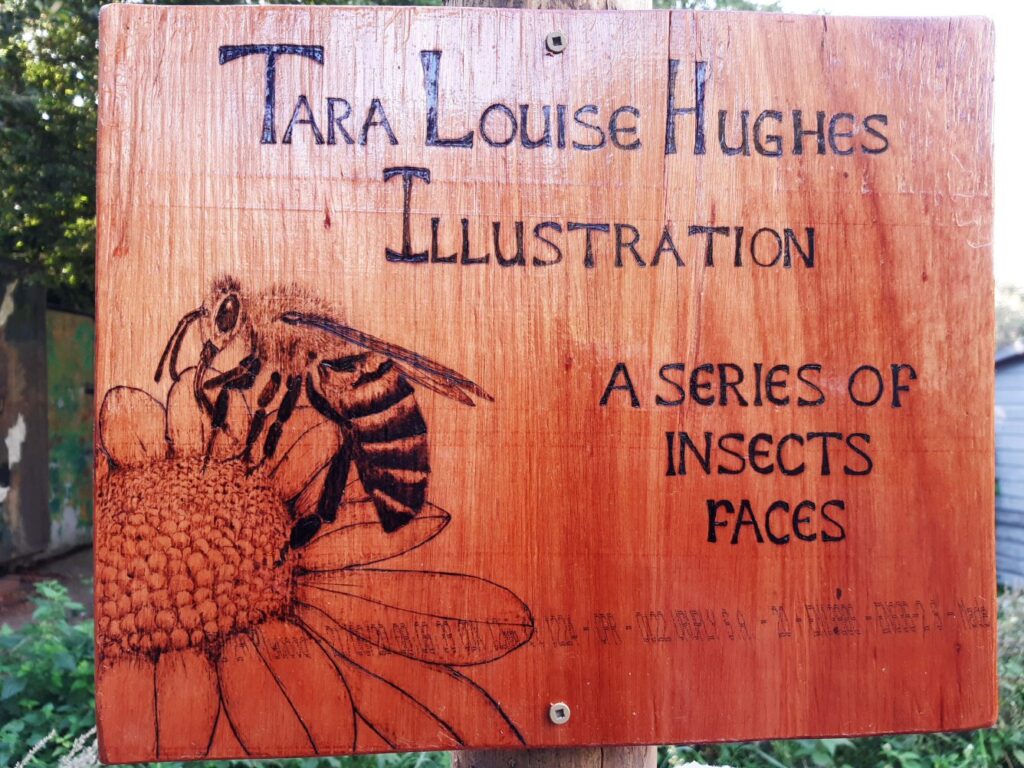

The Gunnersbury Triangle nature reserve this autumn has a new and wonderful nature trail: a series of insects’ faces by Tara Louise Hughes. Tara, when not studying art and illustration, has proven herself a capable conservation volunteer. Now, she has brightened up the reserve for children and adults with her painstakingly fire-etched close-up drawings of insects.

Her damselfly head is a study in miniature detail: the hundreds of pin-point eye-elements (ommatidia) in the insect’s large, forward-facing eyes; the precise distribution and length of the bristles on the top of the head and on the mouthparts; the accurately-observed antennae.

The Stag Beetle head is suitably fearsome, a study in armoured magnificence with interlocking chitin cases for head and thorax, and those extraordinary antler-like mandibles.

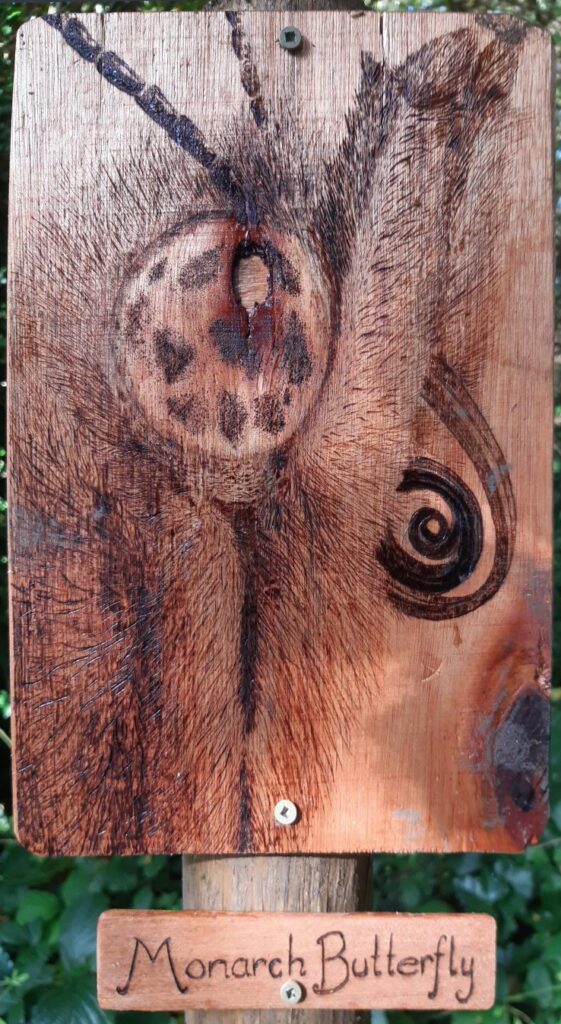

The Monarch Butterfly’s head couldn’t be more different: a study of a delicately furry head, a shy eye, and the tenderly coiled proboscis peeping out on the right.

With the Flesh Fly we’re certainly back in scary territory, the rows of stiffly corseted bristles announcing that this insect is ready for action.

The Buff-tailed Bumblebee, a mild and welcome presence in the reserve, and in gardens wherever there is a suitable supply of flowers. The furry insect seems shy under the artist’s gaze.

If not evil, the Red Wood Ant is definitely fierce and single-minded, as anyone who’s ever been bitten by one can testify. Tara’s fire-etching has brilliantly captured that take-no-prisoners energy with the insect’s smooth bullet head, businesslike antennae, and efficiently-hinged jaws. Take a careful look at those scorched textures at the top of its head.

Tara’s Tortoise Beetle shows the distinctly tortoise-like carapace from the underside, its knobbly texture skilfully burnt into the wood, the little head jutting out under the curved rim with the antennae cautiously feeling the outside world for possible danger.

Tara’s website is at https://taralouisehughes.medium.com/