There were also Small Whites, Meadow Browns, Gatekeepers, Small Skippers, and possibly Chalkhill Blues about.

Well, this strange year – a cold dry April when the bees could hardly feed for lack of pollen and nectar; the wettest May anyone can remember; and now a June so late that cherries, raspberries and redcurrants are ripening all together. In some recent years, the end of June would have been too late for many flowers, specially on Aston Rowant’s steep, free-draining Chalk Grassland.

But not this year: it’s like Tolkien’s The Shire after Sam Gamgee has returned victorious and sprinkled the magic grains of earth from Galadriel’s Elvish Garden in all his favourite spots, and everything is glorious with colour, buzzing with bumblebees, and glittering with iridescent green Forester Moths, Thick-Kneed Flower Beetles, and astonishingly shiny Hawkweed Leaf Beetles.

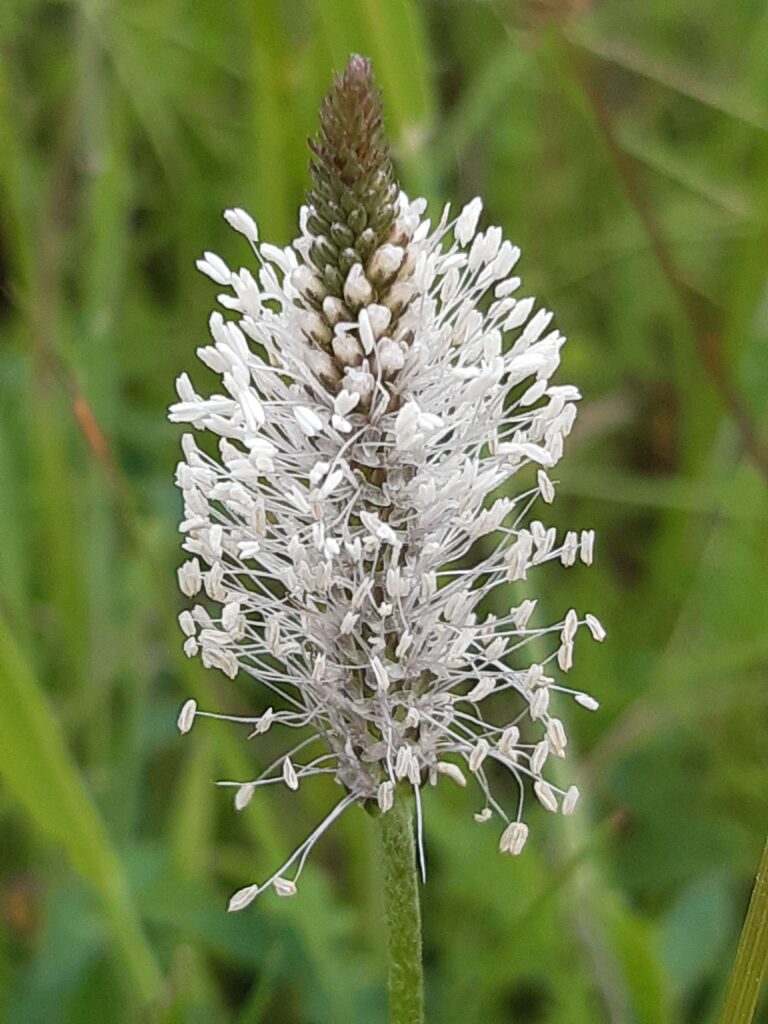

This curious little flower in the Broomrape family, Yellow Rattle, may seem to be just an oddly-shaped herb; but it’s critically important to the flowery meadow ecosystem. It doesn’t have much in the way of green leaves, as it’s a parasite: its roots attach to nearby grasses, extracting the food it needs to live, and in the process weakening the grasses all around it. Result? Tall tough grasses that would otherwise crowd out and overwhelm their attractively coloured neighbours are suppressed, and a wealth of insect-pollinated flowers can, well, flourish. That doesn’t mean the area can just be left to look after itself: Hawthorn and other shrubs would quickly take over and turn the place into forest, so carefully-planned grazing is necessary to keep the land at the meadow stage. It’s called Rattle, by the way, because the ripe seeds dry out and rattle inside the leafy fruit capsules when the plant is shaken.

This small flower was once common in meadows, indeed its name tells its story: it was found wherever milk cattle grazed, in all Britain’s meadows. Now in lowland Britain at least, it’s a rare and special sight, and we feel excited and happy to see it: such is the scale of the catastrophe that has overtaken our countryside. Basically, the flowers are almost all gone; so are the insects; and the birds are fast following them. A place like Aston Rowant is indeed special: its warm, south-facing chalk slopes really were always a wonderful place for flowers like the Chiltern Gentian and butterflies like the Adonis Blue, and happily it still is; but it’s now special just for being what our grandparents would have seen as ordinary: it’s full of what they knew as common wild flowers “of wayside and woodland”.

There weren’t many butterflies about – Meadow Browns, Common Blues, a single Marbled White very handsome with its dancing flight, a good number of Small Heaths up on the hilltop, a Red Admiral. It looks as if the difficult spring has meant low butterfly numbers this year.

My 2014 blog on Aston Rowant, with a different selection of species (and some trenchant thoughts): http://www.obsessedbynature.com/blog/2014/06/18/aston-rowant-beautiful-brutalized/

Ravens, several in aerobatic pairs, wheeled overhead, as did a Buzzard and quite a few Red Kites.

A Bullfinch wheezed its odd “Deu” call from a hawthorn bush as we had our picnic.

Aston Rowant National Nature Reserve is on the scarp of the Chiltern Hills, between Watlington and Chinnor. That places it at the western edge of the relatively hard rock of the Cretaceous period – Chalk – overlooking the softer rocks of the Jurassic period – the Oxford Clay. It has some fine chalk grassland, once a widespread habitat, though most has been lost to the plough, woodland, or development. And it has a rushing noisy motorway right through its middle, complete with a deep cutting hacked through the chalk escarpment. Here’s a short video clip to give you the general idea.

I visited in hope of seeing some orchids, and was delighted to find not only Pyramidal Orchid and Bee Orchid, but some seemingly hybrid plants with a few looking very close to ‘Wasp Orchid’, a variety of the Bee Orchid species.

The site is carefully managed by English Nature to conserve the plants and animals of this special habitat. They employ a team of 24-hour all-terrain woolly mowing machines to keep the grass sward properly short for the more delicate flowers, such as the orchids, the Cistus rock rose, the delicately aromatic tufts of wild thyme, the eyebright, salad burnet, and many others.

The flowers in turn support a wealth of bees, butterflies including (those that I saw) Meadow Brown, Small Heath, Marbled White, Speckled Wood, Brimstone, Adonis Blue and Small Tortoiseshell, as well as day-flying moths like the Cistus Forester and the Six-Spot Burnet.

The delightful grassland is scored by ancient trackways, and the pre-Roman Ridgeway runs along the bottom (surprisingly) of the slope. Which brings us back to the modern trackway, its constant roar doing its best to drown out the bleating of the sheep and the screams of the red kites. The zizz of the grasshoppers is not lost entirely, but the quiet contemplation of them is certainly a little difficult.

So, what are we conserving? Beautiful nature, ancient landscapes, specific habitats, individual species, an experience for the public, material for scientists to study? As the photograph shows, humans have cut trackways through the chalk for thousands of years: it’s just that somehow, an ancient trackway seems a little, well, quieter than the modern variety. The most obvious effect is on human visitors: the place isn’t quite the escape from modernity that it might be.

Beautiful but brutalized: perhaps meadowsweet waving in the breeze under the sunshine on the M40 is the perfect icon for the Britain of Cameron (and Blair before him). We need transport infrastructure, heaven knows, just as we need sufficient housing and everything else. And yet, a reserve where visitors can actually hear the birdsong (and record it if they want to) would be nice, even if the birds do manage to reproduce somehow. Are they affected? They easily might be. So what is a nature reserve for? If it’s a place where a teacher can bring a class and say ‘this is what the countryside was like x years ago’, then Aston Rowant fits part of the bill. Realistically, what do we want our world to be like? Just with one or two pretty bits to conserve the orchids, the cameras judiciously avoiding getting trucks in the background, the video having to dubbed with birdsong and grasshopper stridulation in the studio? Can we afford something more complete, given all the other pressures on the budget? Not easy to say, I think.

Down to Aston Rowant on a fine clear sunny day with a cold East wind that brought spring migrants like the Ring Ousel, a rare blackbird of mountain and moorland. I saw a probable one diving into a juniper bush; they like to stop off on the scarp of the Chiltern Hills as the next best thing to their favoured moors, before flying on to Wales or wherever.

The scarp slope of the relatively hard Chalk falls steeply to the broad plain of the soft Oxford Clay below, to the West. Much of the grassland has been destroyed for agriculture, either falling under the plough or simply being ‘improved’ as pasture with fertiliser, encouraging long grasses at the expense of the wealth of flowers that once covered the English countryside. Happily, here in the reserve and in quite a few places on the Chilterns, the steepness of the land has discouraged improvement. The chalk grassland is dotted with hundreds of anthills, the tiny yellow ants living all their lives below ground, tempting green woodpeckers to come out and hunt for them.

The trees and flowers are visibly weeks behind those of London. The Whitebeam is just coming into its fair white leaves, which look almost like Magnolia flowers in their little clusters newly burst from the bud. But the tree’s name comes from its white wood, not its leaves.

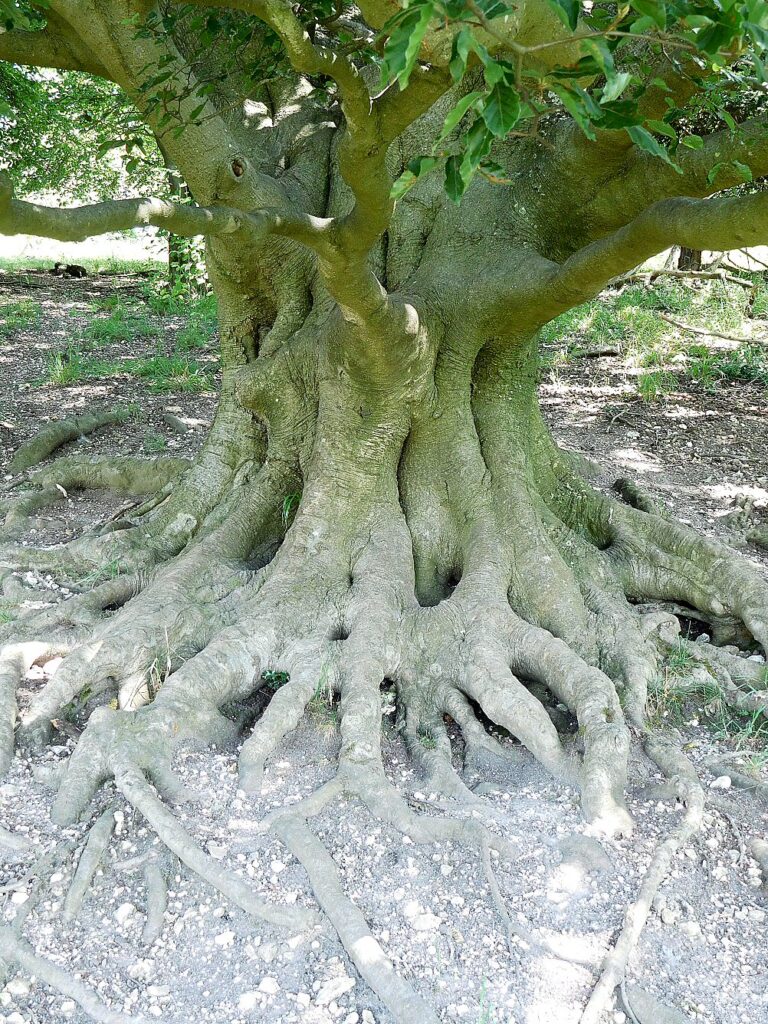

At the bottom of the scarp, a field away from the Ridgeway which follows the line of hills for many miles, Hornbeams and Birches marked a change in the soil, which must be neutral or acid down here, compared to the strictly alkaline rendzinas and brown earths of the chalk. One of the Hornbeams looked as if it was oddly full of Mistletoe, but up close it proved to be a mass of Witch’s Brooms, growths of the tree itself caused by an infection.