September Publishing, 2023. ISBN 978-1-9128-3617-8

You and I have read plenty of nature books that wax lyrical about the beauty of the liminal, the unfathomable gritty reality of walking along a muddy track on the outside of town between the sewage treatment plant, the football stadium, and the business park, and suddenly being transfixed etc etc by the unearthly and astonishingly loud song (for such a tiny bird) of the wren, rising etc etc above the mundane roar of the traffic and the air conditioning fans to transport the lonely naturalist into the unparalleled ecstasy of the mundane.

Fortunately, Two Lights is nothing like that.

James Roberts is an artist as well as a poet. He is lucky enough to live in the quiet countryside of the Welsh Borders: and to enjoy some of the country’s darkest skies, so that he can see thousands of stars, the milky way and comets. And he writes about it simply and beautifully. But no, he does more. He lets his imagination, his atlas of the world, the journeys he made when he was young, what he has read, his father’s decline and death from Parkinson’s, his wife’s journey through breast cancer and radiotherapy, history, the loss of wild places everywhere, take him to different places, and express what everyone is feeling in these crazy times, love and loss and desperation and, yes, beauty despite it all.

Roberts is an experienced artist, with the gift to describe his subject plainly without either getting excessively technical, or talking down to his readers: “Most artists are obsessed with space. Positive space is the area of a picture which contains the subject, the details, the face or figure in a portrait, the arranged objects in a still life, the trees and rocks in a landscape. Negative space is the area of the picture which surrounds the subject.”

He goes at once to the heart of the matter: “I’ve spent hours staring at Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, wondering how he managed to achieve the milky light in the room, the sense of silence, the open-mouthed expression on the pregnant woman’s face and the depths behind it.”

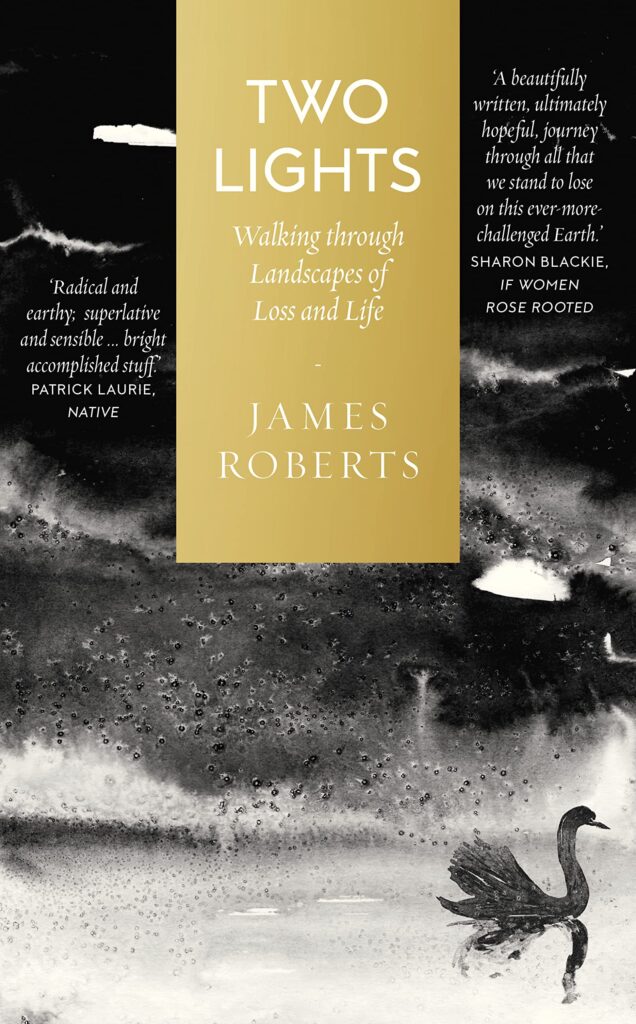

I don’t know about you, but I immediately downloaded an image of the painting – the book’s illustrations are all of Roberts’s own work – and spent several minutes with my new-found knowledge of positive and negative space, wondering how Vermeer had done it all so seamlessly, as if it was easy. Then I wondered how Roberts had written about it all so seamlessly, as if it was easy.

Two Lights begins with a chapter on the dawn, and ends with one on dusk, presumably the two lights of the title. Roberts says he is attracted to these times, these transitional lights, when forms appear or dissolve, when shapes shift, when negative space appears positive or vice versa, when birds sing, when what seems solid and permanent is revealed as constantly changing.

The book’s subtitle, Walking through Landscapes of Loss and Life, speaks of its themes: personal connection to a landscape and its wildlife, to all of nature; and within that, a connection between personal loss and the silent, invisible shockwave of human impact on all of nature, from the paleolithic to the present.

You might think that with global warming, deforestation, overfishing, soil erosion, draining of wetlands, damming of rivers, pesticides, pollution, growth of cities, nights so bright with streetlights that citydwellers never see more than half-a-dozen stars, nights without nightingales, corn without cornflowers, meadows without meadowsweet, hedges without “immemorial elms”, roadsides without primroses, garden Buddleia bushes without butterflies, the extinction of species… that we would need no reminding that we have lost something.

But Roberts is right, we’ve forgotten. Our leaders think of wars and armies, of immigrants and policies, of votes and elections, ignoring what is happening to the world all around them: like officers fighting on the bridge of a sinking ship.

He’s also right that lecturing doesn’t work. Perhaps the oblique, feather-light, razor-sharp insight of an artist and poet may do better.

Roberts walks the bare hills and valleys of Wales, recalling “the forest of my imagination … hiding beneath my feet, in these hills, waiting to regrow.” The trees were cleared thousands of years ago, the first people of Britain burning gaps in the forest to make way for their fields. Now:

“News bulletins have been covering fires in Greece and Italy, and also those in California … on the map, the brightest areas are in Africa. The whole of the Congo seems to be burning, Central and East Africa lit up, Zambia, Angola, Tanzania, Kenya. There are fires in places where it is now winter, in Australia, New Zealand, Patagonia. Even in the cold and wet north, in Siberia, Iceland and Northern Canada, there are blazes seemingly everywhere.”

Of course, in Britain, there’s not much forest left to burn, its 13% coverage the lowest in Europe, its nearly-extinguished wildlife among the most impoverished in the world.

Roberts dreams of the Great Bear Rainforest of the Canadian Pacific Northwest, of its rivers so thick with salmon that they seem to overlap like fish-scales, of its bears fishing in the rich waters, their salmon-enriched scat fertilizing the forested hills for miles around, wild with wolves. The bears and the wolves are gone from Britain now, along with most of the trees and nearly all the salmon:

“This was part of the great border forest, home to the last wolves in England and Wales. There are few stories of them, though they were still here when some of the old oaks which stand in the fields were saplings.”

His wife recovers; Roberts’s depression doesn’t go away. He reflects on a saying of the psychologist James Hillman, that depression is sometimes a right response to a damaged environment; you may feel like that because that’s how things are, “a sign you’re still sane”.

The text is interspersed, accompanied and enriched, by full-page prints of Roberts’s evocative ink paintings. He uses ink, water, and salt which creates dark specks with paler surroundings, random but orderly, wild but controlled, like an ecstatic dancer following the choreographer’s steps but connecting with the hearts of the audience.

Buy it from Amazon.com (commission paid)

Buy it from Amazon.co.uk (commission paid)

I received a review copy of this book.