London Wildlife Trust’s ecologist, Alex, has set about finding out what is actually happening to multiple sorts of wildlife across the Trust’s many reserves, including quite a few that don’t have a warden, or even a group of volunteers. This is quite the task, when you consider that each reserve may contain multiple habitats — woodland, meadow, and pond, for instance — and that each habitat may be monitored for different sorts of beastie, like amphibians or pond invertebrates, and that each site may be sampled in each of several places (different ponds), each with multiple micro-habitats (open water, between plants, …), and each sampled repeatedly through the season.

Alex has set up templates for each type of monitoring in the Memento Database app, which has the merit of being free to download, and of being usable entirely offline if people are saving their mobile’s battery or have a wobbly data connection. We downloaded the app and installed her ‘Aquatic invertebrates’ template.

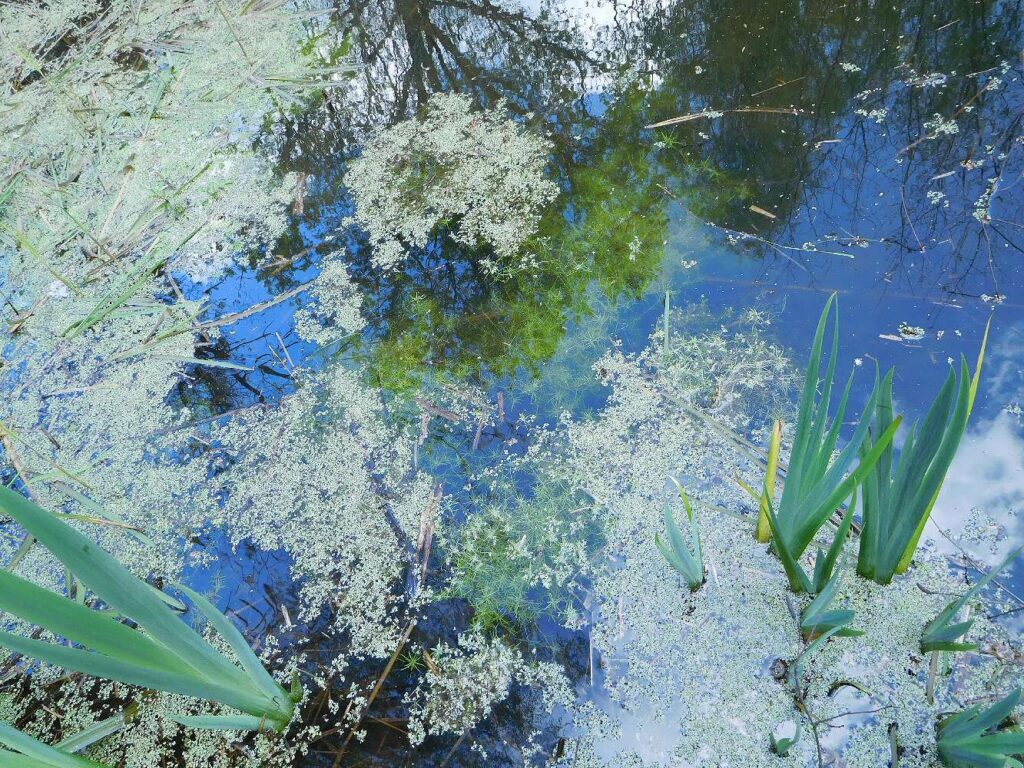

Then we half-filled a plastic tray with pond water and told the template to create a new sample record. We put in our initials, agreed a numbering for our four ponds: the seasonal ponds P1, P2, P3, and the main one P4, and filled in the amount of shade on the water, amount of vegetation, depth of water (the net handle came in handy here as a depth gauge) whether there was rubbish or dead wood or signs of eutrophication or a few other parameters, and then looked VERY carefully at the “water” in the tray to see if there were any beasties in there BEFORE we’d collected our carefully-taken sample. So if you find 5 Daphnia water-fleas in there, you have to subtract that number from your sample when you count it…

One of us — Andy or me — then took the net, swished it about in the chosen area of the pond for 3 seconds, and brought the sample to the tray, carefully washing the net in the tray water.

The template had been constructed for Android. Andy had an interesting time working out how to use it on his i-phone. On my Android phone, it turned out to be a good deal simpler to use, though with three tabs to complete, each with a long list of fields of various sorts, and a nearly invisible SAVE button (the critical bit, really), it took a little practice to get used to it.

The other requisite skill, of course, was being able to see and recognize the little beasties in the water. I thought I’d have no difficulty as I know my Midge larvae from my Mayfly nymphs: but a large number of the pondy bestioles (all technical terms here) turned out to be extra-small water fleas too small to make out clearly without reading glasses (at home, naturally), and too deep in the water to focus on with my hand-lens. So for next time, glasses, and my oversized Sherlock Holmes magnifying glass that someone gave me when I was a teenager — absurdly low magnification, but a wide field of view and a large depth of field. Aha.

The smidgeon-sized millibeasts on which the survey depended (at least on this lovely April afternoon) were the tiniest Daphnia I’d ever seen; equally tiny Cyclops; and (if possible) even smaller Water Mites. My first reaction was, we’ll never manage to ID those things, let alone count them. But you know what? It’s possible, even with a bit of presbyopia. How? Well, the trick is to rely on the “jizz”, the plane-spotter’s “general impression, size and shape” (yes, that must have been “giss” originally, but pronounced jizz anyway), i.e. how it moves, what sort of smudge of colour you can make out, and any hints as to what shape the thing would have if you were actually able to pop it into a watchglass and peer at it properly with a binocular microscope (at home, advisedly).

Daphnia are basically oval, and have a slight reddish hue to them. Cyclops are slender, tapering to a point at the tail, and look greyish. If you’re really lucky, you get a female Cyclops with a pair of obvious egg-sacs either side of her tail.

So you can tell Daphnia and Cyclops apart even if you can barely make them out, because they give a different impression. And, Daphnia swim on their sides, thrashing along with their feathery antennae; while Cyclops swim on their bellies, flicking their antennae like an athlete doing butterfly-stroke with their arms. Both therefore move in little jumps or saccades. The other micro-bestiole that we had in numbers today was the Water Mite. They’ve got 8 legs and a basically round body (the head does not protrude). They swim with their little legs, rather smoothly and continuously … so they don’t look anything like water-fleas except in size.

So we counted the animals in each sample. Coming to the main pond was a pleasure, as it’s a beautiful spot; the sun was warm; and the first thing we saw (rising to the surface of the pond) was a nice big male newt, the first of the year. More, Alex identified it as a breeding Male Palmate Newt, not our usual Smooth Newt: its tail goes down to a point, making it seem relatively short, and its hind feet are webbed.

I added it to the “Notes” field (this was a record of invertebrates). Andy and I found that we were getting used to the template, and filled it in a lot more quickly than our first efforts. I saved and exported the sample record to a .CSV data file, and pressed the email button. To my astonishment I only had to make a couple more clicks and the whole dataset sent itself off to Alex for analysis.